India is burning with protests and counter-protests ever since 12 December 2019 when the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019 (CAA) was enacted and the National Register of Citizens (NRC) and National Population Register 2020 (NPR) gained prominence. I have tried to follow the discussions as closely and as objectively as possible, and I see fundamental flaws at multiple levels, giving me enough cause to vehemently oppose the CAA, NRC, and NPR, especially when seen in combination.

The act of amending the Act

The first question that arises is if there was a need for amending the law through a Parliamentary process when India already has legal provisions to grant citizenship to immigrants based on the merits of their claims? But the answer to this question is found not so much in the legal domain alone, but the politics and ideology of those in power.

The Citizenship (Amendment) Bill (CAB) was first introduced in the Lok Sabha on 19 July 2016. It was referred to the Joint Parliamentary Committee (JPC) on 12 August 2016, and the JPC submitted its report on 7 January 2019 to Parliament. Based on the recommendations, the CAB was revised to include three of the recommendations, leaving out the rest. The Bill was passed by Lok Sabha on 8 January 2019. It was pending for consideration and passing by the Rajya Sabha but it lapsed following the dissolution of the 16th Lok Sabha.

Revisions made in the CAB 2019

(1) the provisions on citizenship for illegal migrants will not apply to the tribal areas of Assam, Meghalaya, Mizoram, or Tripura, as included in the Sixth Schedule to the Constitution. These tribal areas include Karbi Anglong (in Assam), Garo Hills (in Meghalaya), Chakma District (in Mizoram), and Tripura Tribal Areas District. It will also not apply to the areas under the Inner Line” under the Bengal Eastern Frontier Regulation, 1873. The Inner Line Permit regulates visit of Indians to Arunachal Pradesh, Mizoram, and Nagaland.

(2) reduces the period of naturalisation for such group of persons from six years to five years.

(3) on acquiring citizenship such persons shall be deemed to be citizens of India from the date of their entry into India, and all legal proceedings against them in respect of their illegal migration or citizenship will be closed.

The Bhartiya Janata Party had promised to extend Indian citizenship to the religious persecuted minorities from neighboring nations as part of their 2019 election manifesto (see 07, 08, and 12). Following up on their commitment, it was re-introduced in the 17th Lok Sabha on the 09 December 2019 by the Home Minister Amit Shah and was passed on 10 December 2019 (311 MPs voting in favor and 80 against the Bill). The bill was passed by the Rajya Sabha on 11 December 2019 (125 votes in favor and 105 votes against it). Clearly, much of the support in either house was garnered on the party lines, and not strictly on the basis of principles. After receiving approval from the President of India on 12 December 2019, the bill assumed the status of an Act. So with not much opposition in the houses, in three days, the Act came into being.

Composition of the Lok Sabha and Rajya Sabha in December 2019

Lok Sabha (545 seats): National Democratic Alliance (led by BJP) = 338 seats ; Opposition = 207 seats. [Leader of the House – Narendra Modi. Leader of the Opposition – Vacant (since 2014)]

Rajya Sabha (245 (233 Elected + 12 Nominated)): National Democratic Alliance (led by BJP) = 115 seats ; Opposition = 125 seats ; Vacant = 5 seats. [Leader of the House – Thawar Chand Gehlot. Leader of the Opposition – Ghulam Nabi Azad]

Benevolent amendment?

On a cursory look, one may think that the amendment made to the 1955 Citizenship Act is rather benevolent on the part of the Indian government, in line with its humanitarian values, and is meant to be ‘inclusionary’ by offering greater dignity and rights to those persecuted from the neighboring countries currently living in India as refugees or ‘illegal migrants’. The amendment seeks to offer citizenship to those who (1) have been living in India, at least before 31 December 2014, but (2) are from either Pakistan, Afghanistan or Bangladesh, (3) have been persecuted there on the grounds of religion (intent and not in words), and (4) are either Hindus, Christians, Jains, Parsis, Buddhists, or Sikhs. I’ll try to discuss the issues embodied in each of these conditions, from the perspective of equality, to show that the CAA is against the fundamental right to equality, and is largely exclusionary only in a garb of inclusion, potentially to garner popular support.

Article 14 of the Indian Constitution provides that “The State shall not deny to any person equality before the law or the equal protection of the laws within the territory of India”. This equality is guaranteed to all present on the Indian territory, irrespective of their nationality, religious beliefs, caste, class, gender, or date of entry into the country.

Meanwhile, the JPC defends the amendment (page 51) “any legislation may withstand challenge on the ground of discrimination and violation of Article 14 of the Constitution, in case the classification created by it is founded on an intelligible differentia which distinguishes persons or things that are grouped together from others left out of the group, and that differentia has a rational relation to the object sought to be achieved by the statute in question…the positive concept of equality does not postulate equal treatment of all persons without distinction but rather stresses on equality of treatment in equal circumstances as to similarly situated persons and the Bill appears to have the object of facilitating all such members of minority communities without any discrimination”.

This argument is premised on the same reasoning that all affirmative action and personal laws are based on: all in equal circumstances are treated equally. With the following cases, I’d like to prove that identifying people based on the specified grounds, (date of entry, country of origin, cause of persecution and religious affiliation) may indeed exclude some people, where everything else remaining constant, and despite experiencing similar poor circumstances, some people will receive unequal treatment under the CAA and therefore a violation of their fundamental rights.

(1) Date of entry: The specified date of entry (31 December 2014) may exclude many of those who may have moved to India more recently, despite fulfilling conditions 2, 3 and 4. This would mean that these people will be dealt ‘unequally’ for the said law, despite experiencing “equal circumstances”.

Apart from the fact that the same date was notified in the Gazette notification made on 08 September 2015 for the Foreigners Act 1946 (which was based on the last prepared voter list date at that time), it is still largely unclear how the date of 31 December 2014 is still (after 5 years of that notification) being used as a deadline for entry into the country.

Moreover, the documentation required (and available) to prove the entry date into the country would also lead to some erroneous exclusions. For the sake of giving a benefit of the doubt, we can assume that such numbers of immigrants may be very low (although no real data is available for such numbers), and therefore small implications for Type 1 error (i.e. false positives of people getting excluded despite fulfilling the criteria). Considering not much would change for these people from the status quo, it can be argued that the government can deal with this challenge by improving implementation processes, and considering cases on a one-on-one basis through the already-in-place legal provisions of granting citizenship.

(2) Country of origin: The country of origin criterion is relatively more exclusionary, as it does not show similar ‘benevolence’ to other ethnically persecuted communities from countries other than the three mentioned. The amendment does not include the Sri Lankan Tamils (Hindu) who fled Sri Lanka between the 1980s to early 2000s due to systematic violence. Many of them have been settled in Tamil Nadu and other parts of the country since. The numbers may be as high as 100,000 people including at least 29,500 “hill country Tamils” living in Tamil Nadu. This criterion further excludes over 94,203 Tibetans (Buddhist) who faced ethnic persecution in China since the 1950s, and have been living in India in exile for several decades now, without the right to be citizens. Nepalis living in India have also been raising concerns especially after the NRC in Assam declared about 100,000 of them ‘D-Voters’ or doubtful voters. Their concern is valid considering the amendment makes no mention of including them. There are over 1.9 million of them spread across the country, who fear they may not be treated equally after the amendment. Smaller in number, but this condition also excludes other national exiles such as the about 5,000 Ugandan Asians living in India who were expelled in 1972 by the Idi Amin government during its attempt at “giving Uganda back to ethnic Ugandans”. Overall, everything else remaining constant (including fulfilling conditions 1 and 4), at least 2.1 million people will receive unequal treatment, despite their plightful conditions.

[Note: Besides, positioning this amendment as a means to fix the mistakes made during partition, by including millions of citizens of undivided India explains why Pakistan and Bangladesh would be included, but still does not justify Afghanistan. In fact, India does not even share a border with Afghanistan (except PoK). If they were included, then why not African countries like Nigeria and Uganda from where persecuted minorities have escaped over years and found refuge in India?]

(3) Cause of persecution: The criterion of including only those who were persecuted on the grounds of religion excludes all those who are living in exile in India due to other ethnic and political reasons (such as the Tibetans, Sri Lankan Tamilians, and Ugandan Asians mentioned in (2) above). Therefore, despite living in exile in poor circumstances, (and fulfilling criteria 1 and 4), they will still be treated unequally.

Besides, this criterion assumes the premise that the neighboring countries with the Islamist state religions are brutal to the religious minorities living there, and therefore India must give them protection. But this excludes other religious neighbors: Buddhist – Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Bhutan, Tibet; and Hindu – Nepal. It is assumed that religious minorities, including Muslims, are not persecuted there. Also, as explained in greater detail in (4 ) below, some Muslim minorities facing serious persecution in the approved countries of origin are still excluded by the CAA. They fulfill criteria 1, 2, and 3, and yet will be treated unequally.

Further, from an implementation perspective, it may be difficult to prove if one is or isn’t persecuted on the grounds of religion. This may lead to Type 1 error, where although people may fulfill the criteria, they will still be left out due to poor documentation. This would mean that just being of a certain religion and originating from a certain country will be sufficient proof. This, although not as bad as Type 1 error, will also give rise to Type 2 error whereby some of those living in India for reasons other than religious persecution (e.g. marriage), will still be able to become citizens.

(4) Religious affiliation: Religion-based identification criterion is by far the most contentious and ‘unequal’. While it seeks to include those who ‘belong to’ Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist, Jain, Parsi, and Christian communities, it excludes all others. For a moment, let’s keep the equality argument aside, based on the counter-argument being made that the neighboring countries are theocratic (primarily Islamic), and people of certain religions (primarily non-Muslims) are persecuted more than others. Do the numbers justify this claim? According to the Intelligence Bureau, the number of such immigrants from these said countries and religions who are anticipated to benefit from this amendment is about 31,313: 25,447 Hindus, 5,807 Sikhs, 55 Christians, 2 Buddhists, and 2 Parsis (notice there are no Jains in this list, but they are still included in the CAA). That’s about 0.002% of the Indian population.

The largest community this identification criterion excludes is Muslims, even those persecuted from the mentioned three countries on religious grounds. Ahmadiyyas from Pakistan (approximately 2-4 million people from Islamic communities) were declared non-Muslims in 1972 and are being persecuted primarily on religious grounds. They claim to belong to the Gurdaspur district of Punjab in India (the birthplace of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, the founder of the Ahmadiyya Movement) and have been demanding to be allowed to come back. But apart from the fact that they have not been on the Indian land since the cut-off date, they will remain excluded simply because they are not one of the six-religions mentioned. Hazaras (approximately 6 million people) are another large Muslim community facing religion-based violence by the Taliban in Afghanistan but find no benevolence in the CAA. One of the largest refugee crises the world has witnessed in this decade is that of the Rohingyas. Large masses of people, including women, old and children, persecuted from Myanmar on the grounds of religion are facing deep survival challenges. According to UNHCR, about 40,000 Rohingya refugees are in India, and so far the country’s stand is to deport them on the grounds of national security. The CAA does not offer them any respite. There are also reports of atheists in Bangladesh who are persecuted there by fundamentalists who may be looking for refuge in India but will not be granted under the CAA. Given that the objective of CAA is to provide citizenship to migrants escaping from religious persecution, it is not clear why those suffering on similar grounds but belonging to other religious minorities from these countries have been excluded, even when their numbers are potentially much larger. Why are we only ‘benevolent’ to people belonging to these 6 religions?

In conclusion, many, despite experiencing “equal circumstances”, are not being seen “equal before the law” and are differentiated based on certain criteria of religion and origin, and therefore, the CAA violates their fundamental right to equality under Article 14 of the Indian Constitution.

[Note: The BJP 2019 election manifesto had only mentioned “Hindus, Jains, Buddhists, and Sikhs” but then what could have made them add Parsis and Christians? I speculate that since the Parsis, even though small in number, are among the most educated and richest communities in India (think Tatas), excluding them could have far-reaching political and economic repercussions. Kerela, a big political priority for the current government is primarily Christian and (for now) they cannot be alienated.]

[Note: ‘Belonging’ to these communities would mean people need to simply have been born in or married into these communities. They need not be ‘practicing’ or following these religions since there’s no real way to prove religion apart from the family or name unless one has formally converted.]

CAA alone

Let’s even keep the equality argument aside for a while. Let’s give a further benefit of the doubt to the government, and assume that the CAA is indeed meant to be inclusionary, and inclusionary alone. None of the anti-CAA protestors are against giving persecuted communities and vulnerable refugees (in this case ~32,000 people) citizenship. Please be our guests (literally!) and give them the right to dignity, a right everyone deserves (irrespective of the criteria set out).

Extend these ‘illegal migrants’ Indian Citizenship, assuming they want it too. If they indeed do, they can self-identify themselves, approach the Registrar General of Citizen Registration / Bureau of Immigration / Citizenship Bureau / Foreigners Division / Home Ministry, submit the relevant papers, go through the required checks, and get Indian citizenship. And end it at that.

What could be the financial cost of doing that? Assuming a generous INR 10,000 per person (NRC in Assam cost the Indian government about INR 6,400 per illegal immigrant), it will barely amount to less than INR 32 Crore (that would be no more than what PM Modi might have spent on the 60 international travel trips since 2014, in the private jets with security and associated paraphernalia. Tops!)

So, why not just stop at CAA? Why go out and personally search for these people by conducting door-to-door surveys, document checks, and assessments? What would be the financial cost of doing that? The Union Cabinet has recently approved a budget of INR 3,941 Crores to conduct the National Population Register exercise (more on this below), along with the Census 2021, for which an additional budget of INR 8,754 crore is approved. Just to give a comparison, the cost of conducting the 2011 Census was about INR 2,200 crore which works out to a per-person cost of Rs.18.19. Despite the humungous financial cost, the modus operandi chosen is to conduct a survey-based search. Why? Why is it willing to go through even greater social, political and economic costs in the process in the face of nation-wide protests and resistance? Because CAA might be, but the NPR/NRC is certainly not just about inclusion. CAA, framed in the language of inclusion, is simply a pretext to garner support from the otherwise well-meaning but naive citizens (and diaspora) and fulfill other agendas (potentially rooted in the political ideologies of those in power) using ‘simple implementation mechanisms’: NPR and NRC.

[Note: Some people give counter-arguments that the so-called-liberals are opposing the CAA simply because it is led by the BJP. They are reminding everyone that it was originally a Congress’s idea. You know what – nobody cares about whose idea it was. It would have faced similar resistance if they had brought this upon us. But they didn’t. Or maybe people of India didn’t vote for the Congress precisely for this reason, so shouldn’t they feel cheated when the BJP government after winning is still implementing Congress’ ideas… hmm… thoughts? Anyway, I will try and keep my arguments as non-aligned with any political party as possible. Because this is not about party lines, but principles.]

CAA + NRC + NPR = Exclusion

CAA is not here alone. It has in its tow the NRC and NPR. Let’s first establish the relationship between the CAA, NRC, and NPR and if they act together. The BJP speakers and other CAA supporters have constantly maintained that (A) CAA has nothing to do with the NRC and NPR, considering the recent amendment itself does not mention either of these and (B) NPR is simply a ‘regular census exercise’ and is a requisite for all countries to maintain a register of its citizens. But the legal reality is far from this.

(A) In 2003, the BJP Vajpayee government had introduced the Citizenship

(Registration of Citizens and Issue of National Identity Cards) Rules, 2003 as part of the Citizenship Act, 1955. These rules define and establish the National Population Register (see section 2(l)) as well as the National Citizenship Register (see sections 3). A simple reading of these rules further establishes that the NPR will form the basis of the NRC (see section 3(5)).

Extracts from the 2003 Rules that define the NPR and NRC and their connection

Section 2(l) : ‘Population Register’ means the register containing details of persons usually residing in a village or rural area or town or ward or demarcated area (demarcated by the Registrar General of Citizen Registration) within a ward in a town or urban area;

Section 3(1) : The Registrar General of Citizen Registration shall establish and maintain the National Register of Indian Citizens. (2) The National Register of Indian Citizens shall be divided into sub-parts consisting of the State Register of Indian Citizens, the District Register of Indian Citizens, the Sub-district Register of Indian Citizens and the Local Register of Indian Citizens and shall contain such details as the Central Government may, by order, in consultation with the Registrar General of Citizen Registration, specify.

Section 3(5) : (5) The Local Register of Indian citizens shall contain details of persons after due verification made from the Population Register.

Note that the NPR need not always be accompanied by an NRC. The first nationwide NPR exercise was conducted in 2010, although this was not followed by an NRC. But the inverse is not true. A nationwide NRC cannot be established without conducting the NPR, making it a necessary condition, and which will eventually form the basis for who will make it to the National Register of Indian Citizens or not. Therefore, although seemingly simple instruments of implementation, NPR and NRC have far-reaching implications on an individual’s citizenship status.

The rules also make reference to the identification of “doubtful citizens” (see section 4(4)). This is arbitrary and left at the discretion of the surveyor and subjective interpretation of the administration. The “doubt” can arise out of anything – presence/absence of documentation, the sufficiency of documentation, plausibility of the documentation, or any other reasons deemed fit by the surveyor. In such “doubtful” cases identified, Section 5(a) further puts the onus of proving their citizenship on the people, on which decision would be taken in 90 days. This particular clause single-handedly can be used as a means to delegitimize someone’s citizenship status. Although these rules don’t explain any further on what happens to those who are identified as “doubtful citizens” in the NPR, it potentially has implications for these people to be included or excluded from the NRC.

Extracts from the 2003 Rules that establish the category of ‘doubtful’ citizens

Section 4(4) : During the verification process, particulars of such individuals, whose Citizenship is doubtful, shall be entered by the Local Registrar with appropriate remark in the Population Register for further enquiry and in case of doubtful Citizenship, the individual or the family shall be informed in a specified proforma immediately after the verification process is over.

Section 5 (a) Every person or family specified in sub-rule (4), shall be given an opportunity of being heard by the Sub-district or Taluk Registrar of Citizen Registration, before a final decision is taken to include or to exclude their particulars in the National Register of Indian Citizens.

This gets us to yet another important amendment that will have implications here. In 2003, by the same Vajpayee government, another significant amendment was made to the Citizenship Act 1955: the introduction of the term “illegal migrant”. According to this, “an illegal immigrant is a foreigner who: (i) enters the country without valid travel documents, like a passport and visa, or (ii) enters with valid documents but stays beyond the permitted time period. Illegal migrants may be imprisoned or deported under the Foreigners Act, 1946 and the Passport (Entry into India) Act, 1920. The 1946 and the 1920 Acts empower the central government to regulate the entry, exit and residence of foreigners within India.”

Once identified as ‘doubtful citizens’, and unlisted as ‘usual citizens’ from the NRC, these people become ‘illegal migrants’. This is also when the CAA kicks in again. As long as you belong to any of the 6 religions, you may be rescued by the CAA and regranted citizenship, but it does not safeguard Muslims and people belonging to other faith groups the same way, and maybe further disproportionally represented in this group of ‘doubtful citizens’ and ‘illegal migrants’.

Therefore, CAA has a dual function. While it can work independently of the NRC and NPR, but with them, it offers an additional route to citizenship but only to the 6 stated religious communities, by [plausibly] offering them a recourse of a lower burden of proof. As the graphic below explains, the CAA disproportionately excludes those not from the 6 said religions in the process of proving citizenship. This promotes a citizenship regime based on religion, the first in ‘secular’ India.

Graphic source: Collective authorship – translations available in Hindi, Kannada, English, Telugu, Tamil, Urdu, & Marathi (via by Gautam Bhan)

Meanwhile, apart from the 2003 Rules and CAA, there has been a recent amendment made to the Foreigners Act, 1946 called the Foreigners (Tribunals) Amendment Order, 2019, which now authorizes the District Collector or the District Magistrate (see section 2.A.a), who are also in charge of the NPR-NRC, to refer the ‘excluded’ (those unable to provide sufficient documentation to prove citizenship) to a Foreigners Tribunal. These not-usual-citizens or ‘illegal migrants’ and can then be deported [Note: although not sure to where because many of them native to India wouldn’t have actually come from anywhere else but India] or worse, sent to detention centers.

Extract from the 2019 Foreign Tribunals amendment order

Section 2A(a): for the words “the Central Government may,”, the words “the Central Government or the State Government or the Union territory administration or the District Collector or the District Magistrate may,” shall be substituted

(B) Don’t make the mistake of assuming that NPR is a ‘regular census process’. Census is conducted under the Census of India Act, 1948 whereas the NPR is mandated under the Citizenship Act, 1955 (as pointed out in the 2003 amendment above). While providing information to Census is voluntary and does not require document verification, not complying with NPR has penal consequences with fines (see sections 7 and 17 of the 2003 rules) and it would require the furnishing of documentation (e.g. proof of place of birth of self and parents) (see section 8). In practice, NPR is a ‘Schedule’ or a list of questions that may be asked at tandem with the Census house listing survey questions, even though they are meant for completely different purposes and governed by different laws. Census data meant for counting is aggregated (with no way of recognizing the individual-level information) and published as such, whereas the NPR data with an individual’s information will be used for the purposes of creating and publishing the NRC, through which the lists of inclusion and exclusion could be viewed online.

Extract from the 2003 Rules that make NPR mandatory

Section 7: It shall be compulsory for every Citizen of India to assist the officials responsible for preparation of the National Register of Indian Citizens under rule 4 and get himself registered in the Local Register of Indian Citizens during the period of initialization.

Section 8: The District Registrar, Sub-district or Taluk Registrar or the Local Registrar of Citizen Registration may, by order, require any person to furnish any information within his knowledge in connection with the determination of Citizenship status of any person and the person required to furnish information shall be bound to comply with such requisition.

Section 17: Penal consequences in certain cases – Any violation of provisions of rules…shall be punishable with fine which may extend to one thousand rupees.

Assuming that we still go with the argument that NRC is a register of citizens that all countries must own, and therefore so must we. But wasn’t that the purpose of Adhaar? Why not strengthen that process instead? Some will counter-argue, I presume, that since that is still a voluntary exercise (although for all practical purposes it isn’t anymore) it leaves out all the other residents who continue to live on the land as illegal migrants. So, therefore, this exercise is to go and fix the mistakes done retrospectively by trying to identify and remove all those who are ‘illegal migrants’. So the cost we are willing to incur is indeed to take away (i.e. exclude) some people’s place in the country, strip them of their livelihoods, make them stateless, and take away their dignity (whatever little they have of it). Very ‘benevolent’ investment, indeed.

Another argument often heard is that the ‘illegal migrants’ are a drain to the limited resources. Do we have an estimate of how much that would be, based on which we are willing to make such large investments to curb the ‘infiltration’? Not really. We don’t even know how many illegal migrants there are, who they are (after all that’s why this exercise), and obviously have no estimates of what proportion of resources they are consuming. So this argument is merely a speculation.

Most certainly, the ‘illegal migrants’ put together are not draining as many resources as this NRC exercise as an attempt to removing them will. In truth, illegal migrants make up one of the poorest and most marginalized communities in India. They take up work others are not willing to do at wages no one else is willing to accept. They live in poor conditions because they are unable to access services meant for citizens. They are most certainly not stealing the resources, rather far from it. They are possibly subsiding our privileged lifestyle and system. But unfortunately, for now, they are used as a bait for fulfilling the bigger ideological agenda of those in power.

Instead of going and finding and deporting these illegal migrants, why don’t we just accept that our borders have not been managed as well in the past, and our birth and death record management has been dismal? Why don’t we spend these resources and energy in making these systems more efficient, and monitoring more effective, so going forward we don’t continue having the same doubts (or worse conduct this exercise again after 10 years)? But there’s hardly any investment being done on that front.

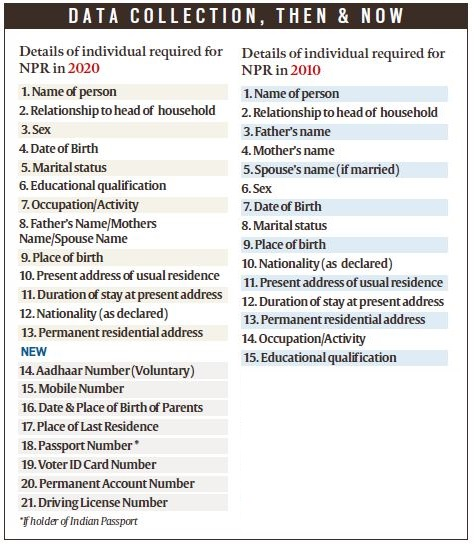

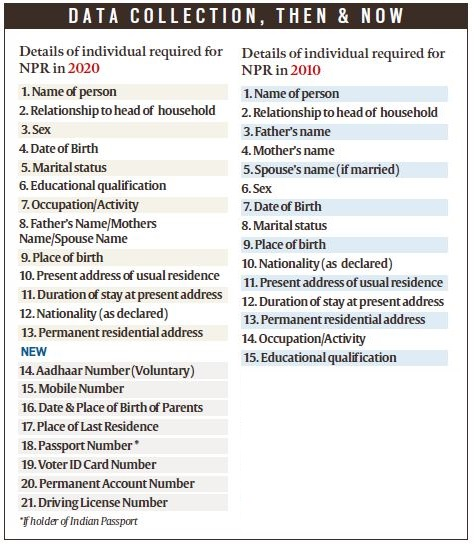

A question that may be raised is why wasn’t the NPR 2010 opposed the same way as the NPR 2020 is? Because there are seemingly minor but additional data points added that can have far-reaching consequences. What are these key differences in data collected between NPR 2010 and 2020? The questions asked under the NPR 2010 is available, but NPR 2020 questions can so far be gleaned from the NPR pilot announced in West Bengal recently. Broadly the key difference is in the additional information required on the date and place of birth of parents which for the first time can be linked with other biometric information of the individual such as Aadhaar. Other information such as religious affiliation, even though also asked for earlier, will also now be linked to a person’s identity and location. The government is then free to make use of this information in any way it wants for the NRC and target them in any way. Note that there are currently no manuals publicly available for training the Census enumerators for conducting the NPR or to know what documents they would be checking. Is this vagueness also deliberate?

Lessons from the NRC conducted in Assam

The nationwide NRC is different from that conducted in Assam, based on the special exemptions made for Assam. As per this rule, the NRC in Assam is completed by “inviting applications from all the residents for collection of specified particulars relating to each family and individual, residing in a local area in the State including the citizenship status based on the National Register of Citizens 1951, and the electoral rolls up to the midnight of the 24th day of March 1971”. Whereas, the nationwide NRC will be based on enumeration conducted as NPR.

Following the notification made on 05 December 2013, the process of NRC was initiated in Assam and was originally meant to be completed in 3 years. By 2015, 3.3 crore people submitted an application to be included, of which only 2.8 crore people were found eligible by 2018. Further, 36 lakh people filed against exclusions. The final NRC listed about 19.1 lakh people, who could either not provide sufficient proof or who did not file the claims. Following this final NRC publication, these now stateless people were asked to file claims to the Foreign Tribunal. What was originally an exercise to determine “illegal migrants” became an exercise on proving citizenship.

All those who had been ardent supporters of the NRC as a means to deal with the issue of “illegal migrants” in Assam found the final number of people excluded to be either too small or disproportionally higher with non-Muslims and therefore demanded reconsideration. The BJP, which is in power in the state, too opposed the NRC in its present form, pitching for 20% re-verification of the names claiming that most people, especially those bordering Bangladesh, have used fake documents to prove citizenship. The exercise took several years, 52,000 government employees, and Rs. 1,220 crores, all to no avail. What is the chance a similar failure may not occur in the nationwide exercise? Low, at best.

Who is likely to get affected by the NPR and NRC?

Make no mistakes. The NRC/NPR will not just affect Muslims. It will affect all, but most of all the vulnerable minorities. The implications will be inversely proportional to socio-economic privileges, level of education and documentation. Rural populations may be more disproportionately affected than their urban counterparts. Dalits will be worse-off than dominant castes, women more than men and transgendered more than cis-gendered. Informal workers more than formal workers, and tribal communities possibly worst of all. But eventually, each and every person will have to go through the trauma of proving your position in the country, at costs that would go well beyond financial.

Hurried implementation

Implementation of the National Population Register is being done on the sly. A pilot was announced to be conducted in West Bengal but faced resistance. As per the recent extraordinary gazette notification by the Ministry of Home Affairs, the NPR “with house-to-house enumeration throughout the country (except Assam) for collection of information relating to all persons who are usually residing within the jurisdiction of Local Registrar shall be undertaken between the 1st day of April 2020 to 30th September 2020.” That is a year before the Census is meant to be conducted (2021).

Meanwhile, many state governments [curiously all BJP led] including Karnataka and Assam, have already started adding to the already existing detention centers, some claiming them to have ‘no links with the NRC’. Is this purely coincidental that they are getting built soon after the CAA is passed? The conditions of living in a detention center will be an entirely new debate enough for an article of its own, but some already emerging examples highlight that public buildings available are being repurposed for this new function, which may be extremely small to house the number of people anticipated, creating conditions of extreme overcrowding, leading to unhygienic and even inhuman living environment.

Then are the anti-CAA protests valid?

In a large country fraught with corruption and illiteracy, limited resources and poor development indicators, high inequity and skewed power dynamics, the trade-offs of conducting a massive exercise such as this can have grave long-term social, economic, and political implications. Let’s weigh in the costs and supposed benefits to see if resisting these changes is worth the effort.

Benefit – 31,000 people will get citizenship and with that more dignity and a right to vote. Some even argue that this number might be higher given that some may have been hiding for all these years but will now emerge considering they are legitimized. But all this can still be achieved without incurring any of the following costs by simply stopping at the CAA, and not proceeding with the NRC/NPR.

Costs – There will be financial, social, political, and environmental costs associated with this. If the government does proceed with the NRC/NPR, the financial cost of conducting the exercise at present is budgeted at INR 3,941 Crores. To give context, the government spent INR 1220 crore in the Assam NRC alone (approximately Rs 6,400 per illegal migrant) and yet failed miserably. Hence, there is no guarantee that after spending all these financial resources, the said objective of identifying ‘illegal immigrants’ will be achieved (at least not fairly).

Even if we assume no malafide intentions on the part of the government behind these recent set of actions, simply the errors as faced in any administrative process can still have far-reaching consequences. The State of the Aadhaar report by IDInsight indicates that demographic error-rate in Aadhaar self-reporting was 8.8% vs. 5.7% for voter ID. These errors may be simply due to mistakes in name, age, address or other required information. In the case of NRC in Assam, a small spelling error in the name led to exclusions from the list. Even if the lower of the two error rates were assumed, it would still mean 74 million people may get erroneously left out from the NRC and their claim to Indian Citizenship delegitimized. An exceptionally superior implementation compared to some of the Nordic governments, would still mean an error rate of 1%, which in the case of India is still a significantly large number – 13 million people. Following the CAA, not all will be at equal risk, despite being left out erroneously. People not belonging to the 6 said religious communities will have no real recourse.

According to the last Census 2011, India had people from groups that do not conform to the six religions mentioned in the CAA. People belonging to Judaism, tribal religions, Baha’i faith, as well as those who did not state their religion make a total of 1% of the Indian population (13 million people). Muslims make up 14.2% of the population. [Note: these are based on what people stated at the time of the Census Survey, apart from what the surveyor may have noted based on the signaling from the names]. Even if only 1% of this 15% are unable to prove their citizenship during the NRC process, and are also unable to find a safety net in the CAA, it would imply an statelessness of over 1.9 million people (a very conservative estimate), their loss of dignity, right to vote, and to a large extent their lives.

Where would these people go? The cost of building one detention center for 30,000 people is 46 Crores (i.e. INR 1600 per person). The financial cost of building similar detention centers to house 1.9 million people alone would mean INR 3 billion. This does not account for the cost of land which is already a scarce resource. It also does not account for the operations and maintenance, after all, as seen from the case of Assam it will take several years to resolve these issues, and there will be both social and financial costs of that.

More significantly, all these financial costs are at the same time opportunity costs on development. What alternative uses could these resources have? Investing in quality education, creating more jobs, improving health systems and roads to access all these, providing safe drinking water and sanitation systems, and indeed making ‘Bharat Swatchh’.

All these excluded people (irrespective of whether they are legal/illegal/religious/non-religious) overcrowded in detention centers are likely to face extreme trauma and indignation. Such living conditions violating human rights might attract a global political backlash, which may have second and third-order repercussions for the country’s economy. But most importantly, the potential for an assault on so many people is so high, that any supposed benefit cannot be worth these serious implications.

Let’s not make the same mistake as we did during the demonetization exercise, where we agreed to pay a price in exchange for reducing corruption, black money, and counterfeit notes. Yes, we paid the price. Many lost productive hours standing in ATM queues, many (especially women) lost financial security, some even lost lives. Many small enterprises shut shop. Banks lost several hours and resources processing exchanges and reprinting new notes. And we as a nation lost economic growth. What did we achieve in exchange? Some counterfeit notes. Worth it? You decide for yourself.

In light of this discussion, it is fairly clear why so many people are out on the streets trying to stop the government from taking such knee-jerk actions, which can potentially have wider grave consequences than benefits for a few. The nation-wide peaceful protests are not to prevent certain people from getting citizenship. They are to protect the ones who have it but fear the risk of losing it.

[Note: The BJP speakers and many supporters are blaming the opposition for instigating protests across the country. A simple common-sense tells me that if the opposition indeed had that kind of power to get people out on the streets, they wouldn’t have been in the opposition but running the government. The other argument people are making to support the CAA is that they are against violent protests. So are the protestors. After all, who does violence benefit? Not the protestors who get beaten up. Not the opposition, because they are on the same side as the protestors and beating them up to silence them would hardly make sense. And isn’t violence a convenient distraction from the key issues at hand? Why is it that most of the violence is happening in BJP led states?]

India’s position on citizenship, illegal migration, and refugees

Citizenship in principle is inherently a paradox. It is both inclusionary and exclusionary at the same time. To keep some people in, many are kept out. The process of making a list of citizens in itself will also delegitimize many. The list can further be used as an instrument to harass people, instigate fear, and spark violence.

Despite its size and claims of being an economic power, India is way lower in the rankings for hosting refugees than its neighbors Pakistan and Bangladesh. According to UNHCR “While India endorsed UNHCR’s Global Compact for Refugees (GCR), the protection environment facing people of concern to UNHCR is expected to remain quite restricted in 2020. Refugees can be expected to continue receiving exit orders, be at risk of detention and face return to their countries of origin. Opportunities to achieve self-reliance and economic inclusion for people of concern will remain limited.”

Meanwhile, India lacks a holistic refugee policy. In the absence of such a law, there is no mechanism available with the Government to determine who a refugee is, and what should be their rights and India’s responsibility towards them. While CAA on the cursory look seems to be inclusionary, played in conjunction with the NRC and NPR, it is extremely exclusionary and unequal and can produce many more refugees than there already are. And once they are, we don’t have a mechanism in place to deal with them.

In the end, NRC may not just be a means to exclude Muslims or make social divisions based on religion. It will be a means to start the process of ‘othering’, which has no end unless we end it now.